- Free Consultation: (213) 251-5533 Tap Here to Call Us

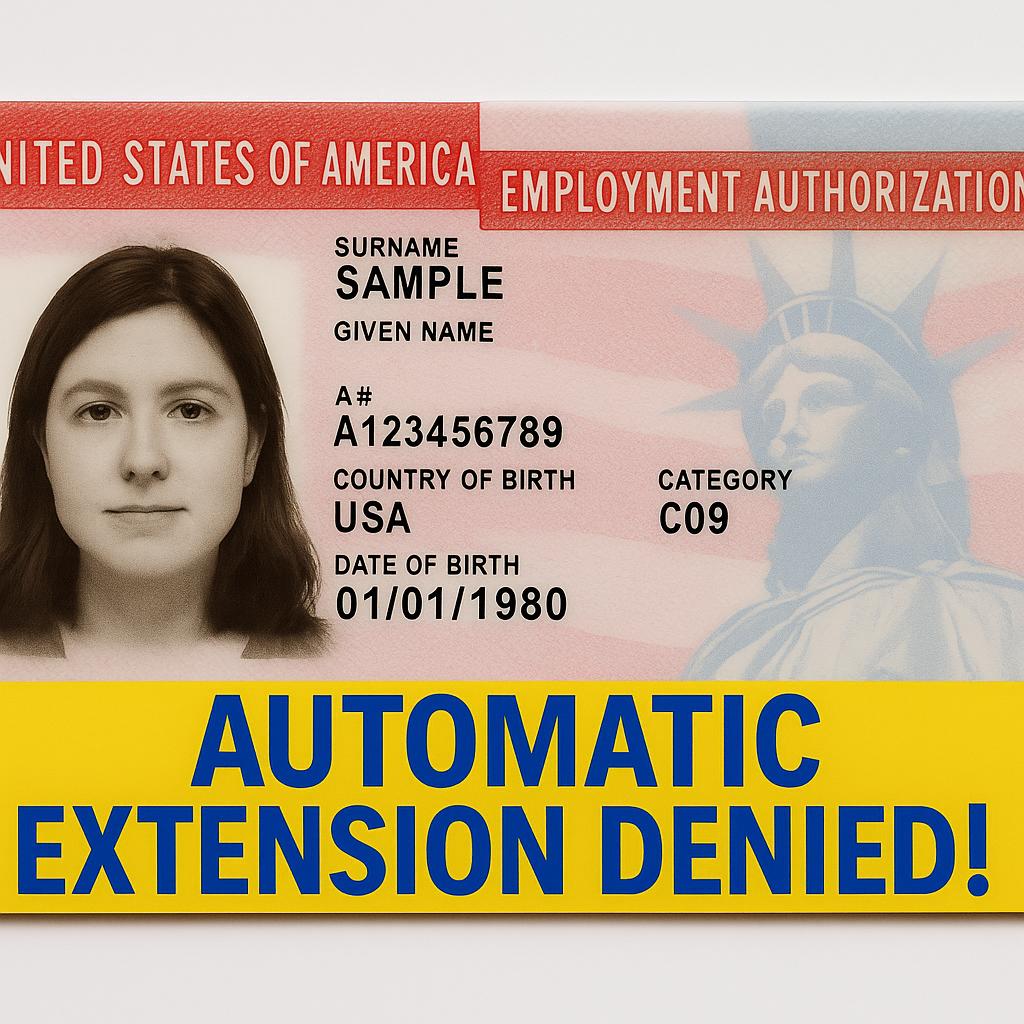

NEW Critical Change to USCIS Rule About Employment Authorization Documents: No More Automatic Extensions!

The interim final rule published by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) as part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) regulatory agenda (DHS Docket No. USCIS-2025-0271; RIN 1615-AD05) fundamentally alters the framework for automatic extensions of Employment Authorization Documents (EADs) for renewal applicants. The rule amends 8 C.F.R. § 274a.13 and related provisions, effectively narrowing the safety net that noncitizen workers and their employers have relied upon when renewal applications (Form I-765) are pending. The shift demands careful attention from individuals seeking work authorization and from employers whose operations depend on legally authorized employment in the United States.

Under the prior regulatory regime applicants who timely filed a renewal of their EAD under certain eligibility categories could continue working past the expiration date printed on their EAD card because of an automatic extension mechanism. See 8 C.F.R. § 274a.13(d)(1)(i) (as amended) and USCIS guidance. The interim final rule signals that for renewal filings on or after the effective date of the rule, unless a separate law or Federal Register notice provides otherwise, the expired or expiring EAD will not automatically extend simply because the renewal was timely filed. The rule thereby heightens the risk of work-authorization gaps—and consequent immigration or employment vulnerabilities—if the renewal is delayed, mis-filed or falls outside the eligible categories.

The statutory authority for this regulatory change can be traced to INA § 274A(h)(3)(B) (8 U.S.C. 1324a(h)(3)(B)), which authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security to extend employment authorization for noncitizens in appropriate cases, and INA § 103(a) (8 U.S.C. 1103(a)), which grants rulemaking authority. The Homeland Security Act (HSA) § 101(b)(1)(F) (6 U.S.C. 111(b)(1)(F)) supplements the framework by establishing DHS’s mission to preserve the economic security of the United States. The regulatory amendment to 8 C.F.R. § 274a.13 reflects DHS’s shift toward greater control and vetting, rather than relying on blanket extensions of authorization while a renewal is pending.

For potential clients and their employers the practical implications are substantial. First, the removal or limitation of the automatic extension means that if a renewal application is filed on or after the effective date of the rule and no exception applies, the individual may lose employment authorization the moment the EAD expires. Employers in turn must ensure that Form I-9 verification is current, track expiration dates, monitor renewal filings, and avoid continuing to employ someone whose authorization has lapsed. Under INA § 274A(b) (8 U.S.C. 1324a(b)) employers who fail to verify that an employee is authorized to work are subject to civil and possibly criminal penalties. The altered regime therefore raises the stakes for proactive monitoring and compliance.

It is helpful to review the list of EAD categories that the USCIS guidance identifies as eligible for automatic extensions under the previous regime. According to USCIS, the following eligibility categories qualified for automatic extension (subject to filing conditions and regulatory criteria): A03 (Refugee) up to 540 days, A05 (Asylee) up to 540 days, A07 (N-8 or N-9) up to 540 days, A08 (Citizen of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, or Palau) up to 540 days, A10 (Withholding of Deportation or Removal Granted) up to 540 days, A12 (Temporary Protected Status (TPS) Granted) up to 1 year or duration of TPS, A17 (Spouse of principal E nonimmigrant) up to 540 days (or I-94 expiration), A18 (Spouse of principal L-1 nonimmigrant) up to 540 days (or I-94 expiration), C08 (Asylum Application Pending) up to 540 days, C09 (Pending Adjustment of Status under Section 245) up to 540 days, C10 (Suspension of Deportation / Cancellation of Removal / NACARA) up to 540 days, C16 (Creation of Record based on Continuous Residence since Jan. 1 1972) up to 540 days, C19 (USCIS-determined prima facie TPS applicant) up to 1 year or duration of TPS, C20 (Section 210 Legalization (pending I-700)) up to 540 days, C22 (Section 245A Legalization (pending I-687)) up to 540 days, C24 (LIFE Legalization) up to 540 days, C26 (Spouses of certain H-1B principal nonimmigrants with H-4) up to 540 days (or I-94 expiration), and C31 (VAWA self-petitioners) up to 540 days. See USCIS “Automatic Employment Authorization Document (EAD) Extension” guidance. USCIS+1 It must be emphasised that eligibility requires timely filing, matching eligibility category codes, and compliance with other regulatory criteria under 8 C.F.R. § 274a.13(d)(1)(i)-(iii). eCFR+1

Beyond eligibility categories, strategic considerations are significant. The rule change signals a departure from the previous assumption that a pending renewal equates to continued work authorization. Legal advisers must evaluate whether a client’s renewal filing falls under the old extension regime (pre-effective date) or the new rules, whether the client’s category remains covered by a statutory or notice-based extension, and whether fallback employment authorization options exist. Employers must update I-9 practices, train HR staff, monitor EAD expiration dates, and adjust workforce planning to account for potential gaps. The stakes are higher than a simple procedural change because any lapse in authorization may trigger unauthorized employment exposure, loss of employment, adjustment of status complications or other immigration consequences.

Moreover, one assumption merits challenge: that the automatic extension rule always offered a secure cushion for renewal applicants. In fact, only certain categories and only timely-filed renewals qualified; many applicants fell outside the safety net. With the current rule change, the cushion is consciously narrowed or withdrawn unless special notice applies, meaning the risk of employment disruption is real. Another misconception: that employers can rely on receipts and expired cards ad infinitum. Under the amended regime, such reliance may lead to compliance risk unless the extension criteria remain met.

From a client-service perspective it is imperative to communicate clearly that the changed system increases urgency, demands tracking, documentation and proactive counsel rather than reactive filing. The removal or limitation of automatic extension places pressure on renewal timing, accurate category matching, and employer-coordinated verification. It may also heighten the need to explore alternative authorisation categories (such as adjustment of status, change of status, or other non-citizen status routes) if renewal delays or eligibility issues emerge.

In conclusion, the interim final rule alters the landscape of employment authorisation for noncitizen workers and the compliance obligations of employers. It removes, for many renewal filings, the prior automatic extension regime or significantly limits its application. This change underscores the importance of legal strategy, timely action, and careful compliance oversight. Those renewing EADs or employing EAD-holders must regard this not as a minor tweak but as a material shift in exposure to risk. Legal advice tailored to the specific eligibility category, renewal timing, work status and employer compliance context is strongly advised.

Legal Disclaimer

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The content reflects general principles of U.S. immigration law as of the date of publication and may not account for recent changes or individual circumstances. No attorney-client relationship is created by reading this article. Readers seeking guidance or representation on specific immigration or employment matters should consult with a qualified immigration attorney.